For Asia and around the world, India is not simply emerging; India has already emerged. And it is my firm belief that the relationship between the United States and India – bound by our shared interests and values – will be one of the defining partnerships of the 21st century. This is the partnership I have come here to build. This is the vision that our nations can realize together.

– President Barack Obama, during his 2014 visit to India

The United States and India have been entwined from as early as the 18th century. Kindred Nations: The United States and India, 1783-1947 is a photographic exhibition that captures various, beautiful moments of learning, partnerships, and exchanges that took place before India was the country we know today. Consisting of photographs, documents, and ephemera, Kindred Nations is organized in five thematic sections: Searching for Opportunity, Gaining Knowledge and Understanding, Seeking Truth and Unity, Finding Inspiration, and Toward Freedom.

The exhibition launched at the Indian Habitat Center in New Delhi on March 12th, and will be on display for one week before its presentation at the American Center and Library at the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, a building that exemplifies the Indian-American collaboration in design and craftsmanship.

Here are a few images and their stories from Kindred Nations that resonated the most with me:

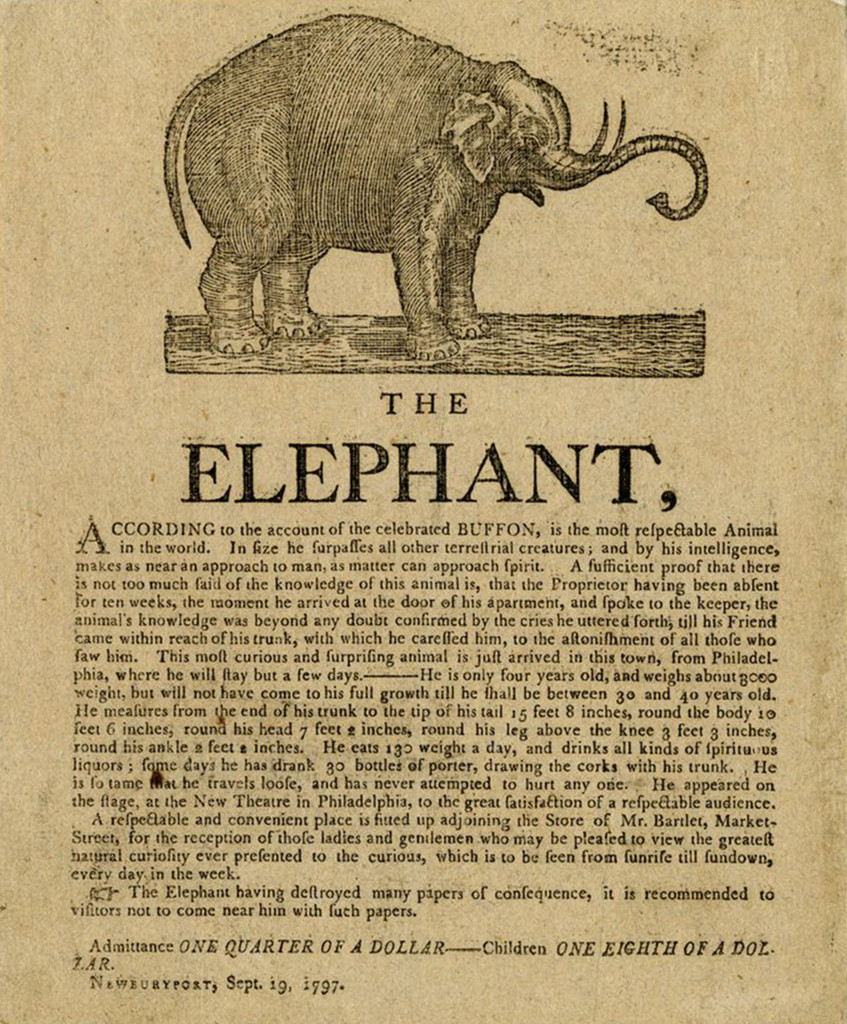

Jacob Crowninshield brought the first live elephant to the United States in 1796 on board his ship America. The two-year-old pachyderm – which the American merchant had purchased for $450 in Bengal – was known as the Crowninshield elephant and was exhibited in cities such as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Salem, Crowninshield’s hometown. Visitors could see the exotic animal for only twenty-five cents, setting a precedent for later circuses to add live animals to their acts. Many speculate that the American nursery rhyme about Miss Mary Mack, who asked her mother for fifty cents to see the elephant, refers to the popularity of the elephant’s U.S. tour. Having grown up in India, elephants were commonplace in my life and in Indian culture for centuries. It was surprising to me that Americans were first introduced to these creatures only in the late 1700s.

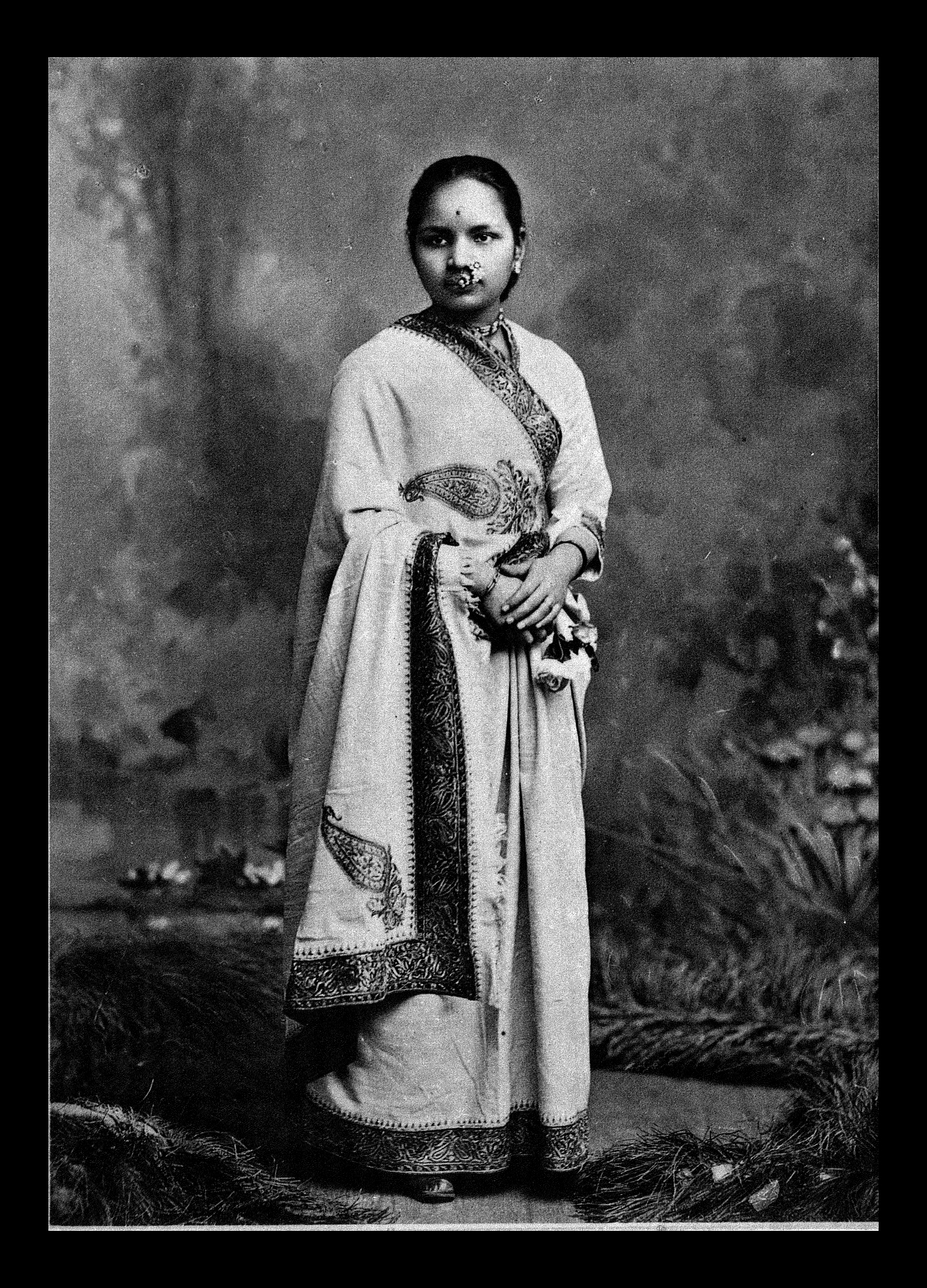

At a young age, Anandibai Joshee was married to a man much older than her. Uncommon, however, was that her husband Gopalrao insisted that she be open to education. When she expressed her wish to study medicine at the age of 14 after losing their first child at 10 days old due to unavailability of proper medical resources, Gopalrao reached out to a well-known American missionary, Royal Wilder, who in turn appealed publicly for Americans to help Anandibai achieve her goal. Theodicia Carpenter, a wealthy American from New Jersey, read about the couple in a newspaper article and offered to sponsor Anandibai’s education at the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, where she graduated in 1886. I see several parallels between my own experience and Anandibai’s as a current graduate student in America who has a supportive husband.

Held in Chicago, the first World’s Parliament of Religions attracted religious leaders from around the globe. There were several lecturers from India, among them Swami Vivekananda, a Hindu of the Vedanta school of philosophy. His famous speech at this gathering played a key role in spreading Hindu philosophy in the West, and Vivekananda was invited to lecture widely throughout the United States. His many wealthy and influential American friends provided funding to open Vedanta Societies across the country. It was interesting to note how the local clergy viewed the event not as a threat to Christianity, but as an opportunity to witness and to learn from other religions. My elementary school had an annual costume competition and one year, I dressed up as Swami Vivekananda and recited one of his famous quotes: “Truth can be stated in a thousand different ways, yet each one can be true.” I won first prize.

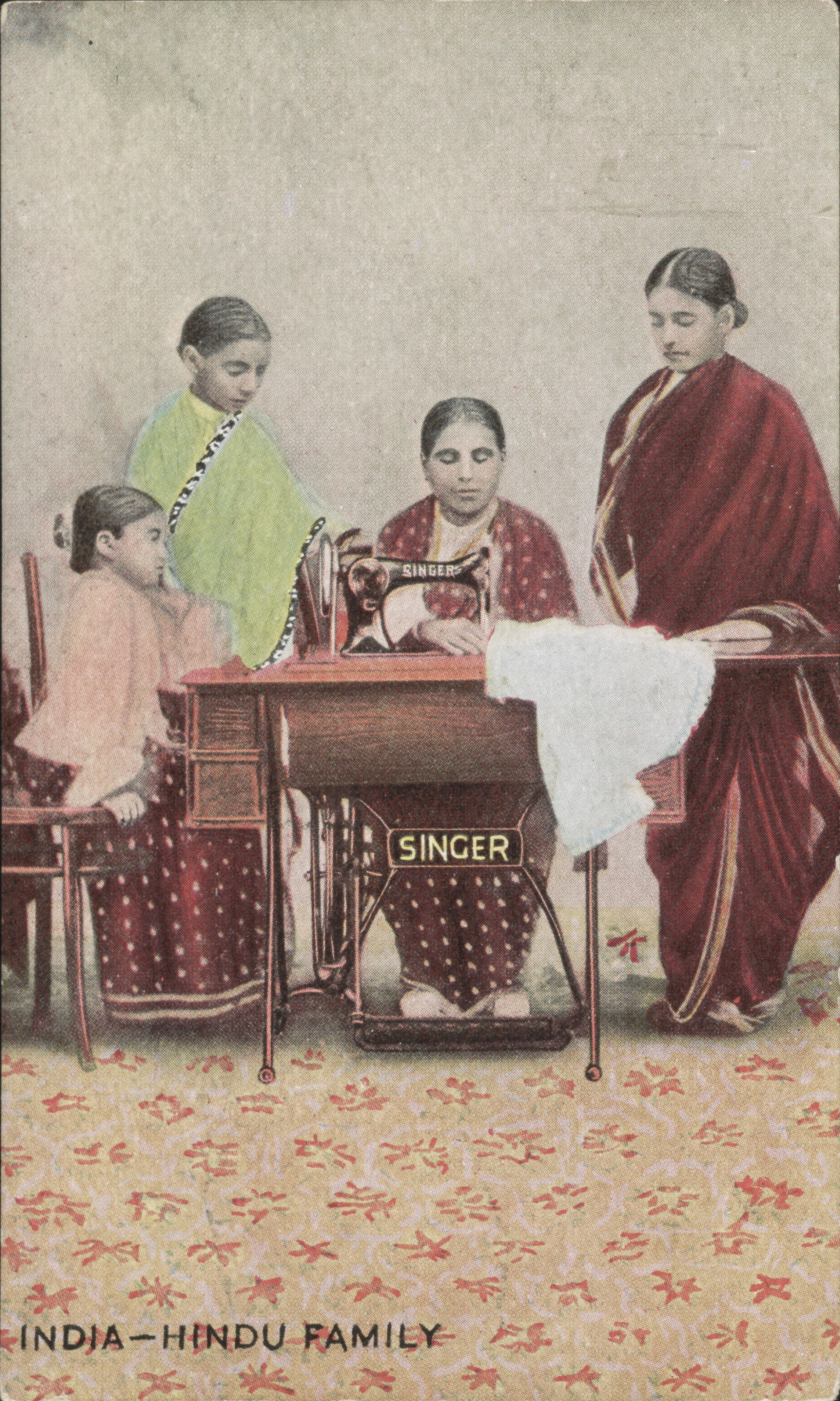

Indian women prided themselves in the ability to sew their children’s clothes, and many still do today. Most middle to upper class households had a Singer sewing machine in their homes. Sewing and embroidery were encouraged as an appropriate pastime for women. The “India – Hindu family” card displayed in Kindred Nations, distributed by the Singer Manufacturing Company, depicts upper class Brahmin women bonding over a Singer sewing machine. My 85-year-old grandmother still owns a Singer machine in her home and has fond memories of the time spent creating designs for our family.

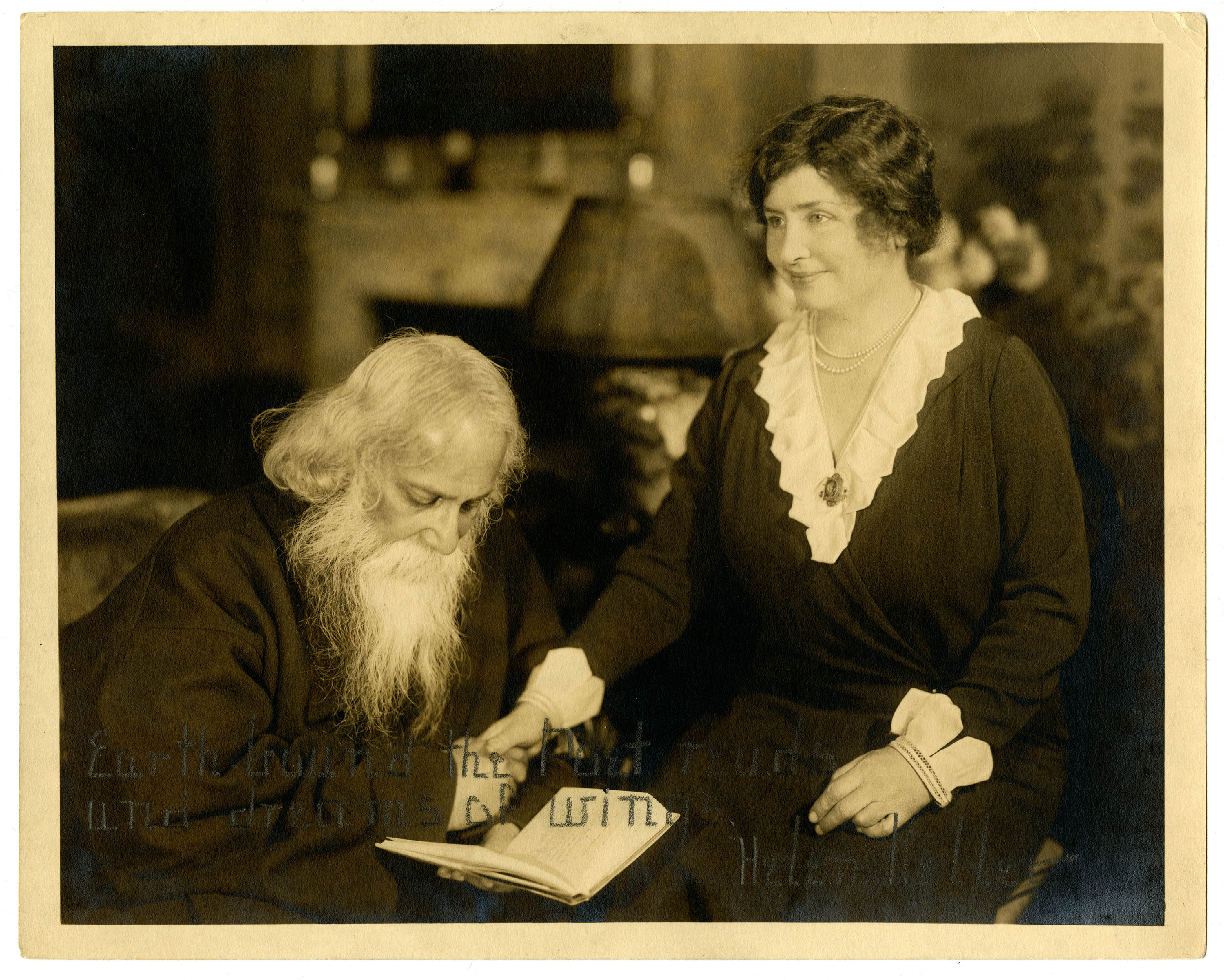

New York, New York; Courtesy of Perkins School for the Blind Archives

Rabindranath Tagore was a highly accomplished, well-read philosopher who reshaped the literature and music of India’s northeast region. He became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913, and was a fierce anti-imperialist and an early advocate of Indian independence from British colonialism. Tagore traveled to the United States multiple times. In 1912, he was invited to speak at a Unitarian church in Illinois, and in 1916, embarked on a lecture tour of Japan and America. During his visit in 1930, he met with activist and author Helen Keller at the New York Historical Society in New York City. During 2013, India celebrated the 100th anniversary of Tagore winning the Nobel Prize. The government, as well as private agencies, commissioned artists from all disciplines to perform at various venues across the nation. Tagore’s works are as revered and relevant today as they were when he created them.

Ananda Coomaraswamy filled many roles during his lifetime, including as a social commentator and Indologist, a historian of Indian art, and a perennial philosopher. These focal points shaped his ideas and writings on history and philosophy. He was fascinated with the problematic relationship of the present to history and of the East to the West. His interest in Indian traditional arts and crafts and presenting it abroad spearheaded an ambitious scholarly enterprise, which led to his position as the first Keeper of Indian Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Coomaraswamy married American artist Stella Bloch in 1922. While they divorced eight years later, they remained close friends. Since moving to the United States 15 years ago, I have actively tried to bridge my Indian culture and my life in the U.S. through dance, while assimilating and raising Indian American children. People like Coomaraswamy remind me that it is possible to have the best of both worlds.

Shimla, Himachal Pradesh; Courtesy of Asha Sharma

Samuel Evans Stokes Jr. was born on August 16, 1882, to a distinguished and wealthy Quaker family in Philadelphia. He was merely 21 years old when he made the journey east to India in his quest to help others. While there, he fell in love with the country and with a local Christian named Agnes. He left an indelible legacy in India in many ways, including introducing American Delicious apples to Himachal Pradesh and serving on the Indian National Congress. Stokes also was the only American to be jailed for India’s independence cause. His story is poetic to me because I have heard of many Indians who migrated to America and became success stories, but learning about an American who made the journey east and started a new life offered a new perspective about opportunity and success.

Bombay, Maharashtra; Courtesy of the Collection of Sukanya Rahman/Ram Rahman

Born in Michigan as Esther Sherman, Ragini Devi had a deep passion for Indian dance. In 1928, she published Nritanjali: An Introduction to Indian Dancing, the first comprehensive book in English on Indian dance. She was instrumental in bringing Kathakali and other dance forms to Europe and the United States and dedicated her life to the pursuit of learning and performing Indian dance. In 1930, Devi traveled to India, where she settled and frequently collaborated with Guru Gopinath, a revered dancer in India and abroad. I myself am a Bharathnatyam (an Indian classical dance form) teacher and performer sharing Indian culture with Americans through dance, and was heartened to learn that this exchange started so many years ago and is continuing with such vibrancy and learning. Interestingly, Devi’s son-in-law, Habib Rahman, was a consulting architect in the design of the American Center.

Calcutta, West Bengal; Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

While stationed in India during World War II, U.S. soldiers enjoyed exploring local sights and observed customs, such as removing their shoes upon entering temples or mosques. This photograph reflects an understanding of different cultures at the grassroots level. The profound simplicity of these soldiers’ acts speaks to the beauty of human nature. Governments may wave the flag of friendship but it is the individual who strengthens and grows this bond. The true testament of the U.S.-India relationship lies in the growing instances of exchanges, partnerships, and friendships of the Americans living in India and Indians living in America.

Kindred Nations is on display at the Indian Habitat Center until March 19th, after which it will be on exhibit at the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi’s American Center. For more information about the exhibition, or to view the complete collection, visit www.meridian.org/kindrednations.