This article is reposted from the Center for Global Development (CGD) (February 23, 2017), which was originally written by Dr. Michael Pisa, Ms. Divyanshi Wadhwa, and Dr. Anit Mukherjee. Pisa is a Policy Fellow researching how technological innovation can support financial inclusion and how the withdrawal of correspondent bank relationships may affect remittance flows. Wadhwa works as a Research Assistant focusing on the unintended consequences of anti-money laundering laws on development. Mukherjee is a Policy Fellow that is currently researching the impact of fiscal devolution on sub-national health financing reform In developing nations including India.

It has been more than 100 days since the Modi government declared that the two largest denomination notes in India—the 500 and 1000 rupee notes—would no longer be accepted as legal tender. The announcement of “demonetization” had an immediate and sweeping effect on Indian households, which were no longer allowed to use the notes (outside of a few narrow exceptions) and were given less than eight weeks to deposit or exchange them. The short-term result was a major disruption in payments and the sale of goods and services reliant on cash transactions, while the long-run effect will depend on what steps the Indian government takes next, including in the realm of digital finance.

The primary goal of demonetization was to flush corrupt money out of the economy, but government officials have increasingly touted another effect of the program: the increased take-up of digital financial services. The government recently underscored its commitment to accelerating this trend when it set a target of having 250 billion transactions processed through digital means by March 2018. That amounts to 200 digital transactions per person in the next 12 months—a tall order indeed.

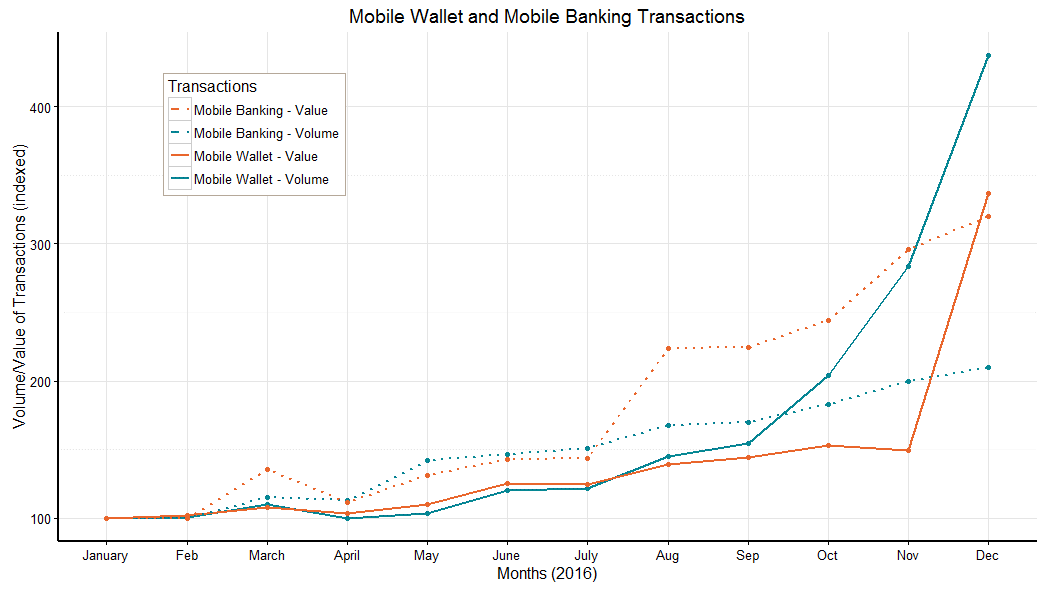

Recent data from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) demonstrate a sharp rise in both the volume and value of mobile wallet transactions between October, the month before demonetization was announced, and December 2016 (see below). While the value of mobile wallet transactions grew by 62 percent, the volume of transactions more than doubled, indicating that small transactions drove most of the growth.

The data jibes with experience at the street level, where small vendors have responded to the cash crunch caused by demonetization by installing apps on their phone that allow them to accept payment through mobile wallets like Paytm. At the same time, mobile banking, which allows bank customers to conduct transactions through their phones, continued to grow at a steady pace.

The benefits of going digital

The appeal to the government of shifting from a cash-intensive towards a “cash-lite” economy is clear: digital transactions are easy for the government to track and tax, whereas cash transactions often escape the “tax net.” Digitalizing financial services could also make government subsidy payments more efficient and transparent. McKinsey Global Institute estimates that together these improvements could boost India’s GDP by 11.8 percent by 2025.

Going digital is also an important part of the Modi government’s efforts to expand financial access to the roughly 33 percent of Indians still outside of the formal financial system. These efforts center around Prime Minister Modi’s Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) initiative, which was launched in August 2014. Under the PMJDY, the government makes subsidy payments directly into beneficiaries’ bank accounts, reducing the hassle and potential delay associated with making and receiving payments through check or cash. PMJDY account holders can also use their phones to transfer funds and receive a debit card linked to their account. Consumers find these benefits appealing: a recent report from CGAP finds that over 260 million PJMDY bank accounts have been opened since the program began.

The success of the PMJDY complements other efforts by India to deepen digital services, including the Digital India Initiative, which aims for universal access to digital infrastructure, and the Aadhaar program, which provides a biometric-linked ID to every resident. The success of these initiatives, together known as the JAM Trinity (short for Jan Dhan Yojana, Aadhaar, and Mobile connectivity) provides India with a platform for broader use of digitally-based services. For example, the state of Gujarat has recently linked its Public Distribution System (PDS) food security program to an Aadhar enabled payment system that allow beneficiaries to pay for their subsidized rations using their ID and linked bank account. Other states such as Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan have piloted the same program in certain districts.

Ensuring sustainability of digital finance: consumer choice, not brute force

Demonetization sparked a one-time move towards greater use of digital financial services, but India’s bigger challenge will be to nurture a more gradual and sustainable shift over time. As CGAP CEO Greta Bull pointed out in a recent blog, despite India’s supportive policy framework, continuing to make strides will ultimately require a huge change in consumer behavior. Ironically, as Bull notes, one of the keys to this transition will be making it easier for consumers to convert digital value to cash (and vice versa). In turn, this will require a major expansion of the network of agents and point-of-sale (POS) machines throughout the country, and a dramatic improvement in internet connectivity, which now reaches only 26 percent of the population.

Even though greater reliance on digital payments has clear long-term benefits for government, industry, and individuals, forcing consumers out of cash is the wrong approach to boosting the role of digital. Instead, as India’s new Economic Survey notes “the transition to digitalization must be gradual; take full account of the digitally-deprived; respect rather than dictate choice; and be inclusive rather than controlled.”

The principle of consumer choice does not preclude governments from encouraging consumers to switch from cash to digital. In fact, using positive incentives to support this transition is rational from the government’s perspective, as the benefits derived from digital increase with scale (“network effects”). The Modi government has tried to entice consumers to make this shift through a variety of means, including providing tax breaks for small traders and businesses that accept payments through banks and digital means, waiving service taxes for digital transactions under 2,000 rupees (roughly $30), and giving discounts to consumers who purchase railway tickets using mobile wallets.

Whether India’s recent rapid growth in digital finance will be sustainable in the near-term is an open question, and it will be interesting to see what happens to the volume of digital transactions after March 13, when the government will remove withdrawal limits associated with demonetization. The longer-term trajectory, however, is quite clear: the shift to digital finance will continue because both the Indian public and private sectors recognize its benefits. The key test for both sectors is to ensure that these benefits accrue not only to themselves but also to the country’s poorest.

By: Dr. Michael Pisa, Ms. Divyanshi Wadhwa, and Dr. Anit Mukherjee, February 23, 2017